Extraorbitant cost keeps HCV care out of reach for many patients: Are there profound ethical and societal issues looming?

Last Updated on March 12, 2016 by Joseph Gut – thasso

[avatar user=”thassodotcom” size=”thumbnail” align=”left” /] March 11, 2016 – Medscape Multispeciality just published a CDC Expert Commentary by John W. Ward, MD, Director, Division of Viral Hepatitis, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia, which addresses the double sided sword of the coming to market of very effective new HCV-therapies and their forbiddingly high cost, which seems to make such therapies, which may cure HCV-infection in most patients in about 12 weeks of treatment, inaccessible for most of the HCV-infection ridden patients. This poses an ethical and societal problem not only in the United States, but even more so in other parts of the world, where HCV-infection rates are high, the patients are poor, and functioning healthcare systems may not exist. Here the statement by Dr. Ward:

Up to 3.5 million people are living with hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the United States, and an estimated 150 million people are chronically infected worldwide. Globally, more than 700,000 HCV-infected people die each year from cirrhosis or primary liver cancer. New cases of HCV infection are also a concern. In the United States, the rate of acute infection has increased by an alarming 150% during recent years, primarily fueled by increases in injection-drug use.

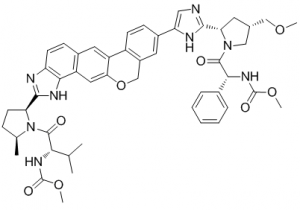

Recent clinical trials have demonstrated that new, simple-to-use treatment regimens for persons living with HCV infection are safe and highly effective, leading to cure in the vast majority of patients—the public health implications of which could be profound. The effectiveness of a combination of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir in patients who have failed to respond to previous treatment and in those with decompensated cirrhosis, a contraindication for earlier HCV treatment regimens, is also very promising, with high rates of cure regardless of HCV genotype.

Given the benefits of safe, easy-to-use, and curative HCV therapy, why be concerned about the impact of HCV on individuals and the public as a whole? The answer is simple: Patients do not benefit from a drug that they cannot afford. Although studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have shown that treating all people currently infected with HCV is cost-effective from a societal perspective, the price of currently licensed medications, at $83,000-$153,000 per course of treatment, is an insurmountable barrier for many.

Despite US recommendations that all people currently infected with HCV should receive treatment, health plans and payers have responded to the high cost of HCV medications by instituting restrictive reimbursement policies. In most state Medicaid programs, only patients in whom the infection has progressed to severe liver disease qualify for HCV treatment. Drug expenditures for the treatment of HCV infection have declined as a result of mandated 23% rebates for Medicaid and privately negotiated prices by health plans, but inequities in patient access to such therapies persist.

To respond to current cost-related barriers to HCV cure and promote health equity, on November 5, 2015, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

(CMS) notified state programs that limitations on drug coverage should not deny access to clinically appropriate antiviral therapy for beneficiaries with HCV infection. CMS also requested that manufacturers disclose value-based pricing agreements so that states can participate in such arrangements.

Beyond affordable drug pricing, benefits of curative therapy can be realized only for persons who have been tested for HCV, know they are infected with HCV, and linked to care. In the United States, at least half of all people living with HCV infection remain undiagnosed. A combination of testing strategies is recommended to identify people with ongoing transmission risks, especially those who inject drugs. Testing is also recommended for people born during 1945-1965 (baby boomers), a population with a disproportionately high rate of chronic HCV. People infected in the distant past are at highest risk of dying from HCV infection. In the United States, even a modest increase in implementation of the CDC recommendation for HCV testing of all people who were born from 1945 through 1965 could avert more than 320,000 deaths when that testing is linked to care and curative treatment.

The care cascade -the progressive steps needed to identify HCV-infected patients, provide them with care and treatment, and elicit cure- is lacking in the United States and in most other countries. A limiting factor with currently licensed therapies is the requirement that HCV-infected persons undergo genotyping and disease staging before the initiation of therapy, complicating and delaying the treatment process. Most HCV-infected people do not receive this level of care. The new sofosbuvir–velpatasvir regimen could simplify HCV management by reducing the need for these steps, paving the way for simple “test and cure” strategies appropriate for primary care and other settings, such as addiction-treatment programs. Educating providers about HCV testing, care, and treatment and creating innovative models for the delivery of care can also increase the robustness of the current care cascade.

The availability of simple, safe, and curative regimens creates opportunities for improving the health of the millions of patients living with HCV infection. At a population level, the effect of HCV medications will be determined by affordability and equitable access to HCV testing, care, and treatment. Only through these improvements can our focus be directed to what matters most: reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with HCV infection, stopping HCV transmission, and ultimately eliminating HCV as a public health threat in the United States and worldwide.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/ Accessed February 23, 2016.

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis fact sheet no. 164. 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164Accessed February 23, 2016.

- Ward JW, Mermin JH. Simple, effective, but out of reach? Public health implications of HCV drugs. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2678-2680 Abstract

- Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Smith BD, Liffmann DK, Ward JW. The cost-effectiveness, health benefits, and financial costs of new antiviral treatments for hepatitis C virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:157-168. Abstract

- American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, Infectious Disease Society of America. Recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C. http://www.hcvguidelines.org/ Accessed February 23, 2016.

- Canary LA, Klevens RM, Holmberg SD. Limited access to new hepatitis C virus treatment under state Medicaid programs. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:226-228. Abstract

- Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. Morb Mortal Recomm Rep. 2012;61:1-18.